“We are the virus, COVID is the cure”: Erasure of Disabled People in the Process of Metaphorizing SARS-CoV-2

by Alicia Leong

ABSTRACT:

It was hiding under your bed. Perhaps it was Slender Man,[1] waiting to stab you. Perhaps it was Momo,[2] lurking, ready to attack. It was haunting, always around, always a threat, but never seen.

It was an object of fear. More recently, public discourses of “the virus,” also known as “the pandemic,” also known as “the rona,” and also known as “COVID,” describe it as the enemy with which we are at war. This is the militarized language disseminated by Andrew Cuomo (1);[3] Cyril Ramaphosa (2);[4] and the director of Colombia’s central military hospital (3, 4).[5] In his press briefing on March 30, Cuomo declared that the “front-line battle is in our hospital system,” identifying healthcare professionals as “the soldiers who are fighting this battle for us” (1).

It was an object of coercion. Using war-like metaphors in the public and private space to understand and represent SARS-CoV-2 and its impact reproduces a “narrow narrative” (5) normalizing war and enabling “shifts towards dangerous authoritarian power-grabs” (1). Not only is it shaped by our assumptions of ourselves, “things” in the world (6), and all the connections in between, language also shapes our interpretations and conversations. Medical terminology has historically generalized, and reduced, non-normative experiences bounded by “individual instances” (7, 8). The metaphor of SARS-CoV-2 as the invisible yet all-pervasive enemy obscures the other metaphors we have constructed to process and share our personal (and collective) experiences in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Those who face “the enemy” become heroes. But what do we do with those of us who wait? Those of us who are stuck in time? As we lose our sense of control, taste, smell, and touch of other bodies, how does this (re)frame our engagement with (dis)ability in representations, language, medicine, and the law?

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

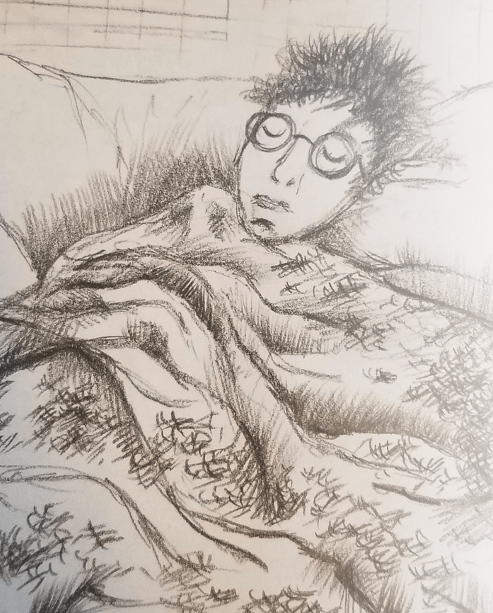

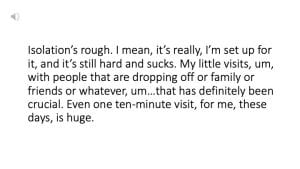

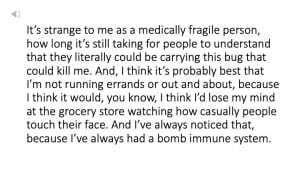

My project explores the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on individuals who self-identify as disabled in societies with persevering ableist tendencies (9). COVID-19’s isolated world is the “norm” for a historically excluded disabled community (10)

SLIDE 2

SLIDE 3

SLIDE 4

SLIDE 5

SLIDE 6

SLIDE 7

SLIDE 8

SLIDE 9

SLIDE 10

SLIDE 11

SLIDE 12

SLIDE 13

SLIDE 14

SLIDE 15

SLIDE 16

SLIDE 17

SLIDE 18

SLIDE 19

SLIDE 20

SLIDE 21

SLIDE 22

Works Cited

- Musu, C. (2020, April 8). Why It’s Dangerous to Use War Metaphors to Describe Coronavirus. The National Interest; The Center for the National Interest. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/why-its-dangerous-use-war-metaphors-describe-coronavirus-142192

- Neuman, S. (2020, March 27). South Africa Reports First COVID-19 Deaths, Goes Into 3-Week Lockdown. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/03/27/822363982/south-africa-reports-first-covid-19-deaths-goes-into-3-week-lockdown

- Noguera Montoya, S. P. (2020, March 28). El Hospital Militar de Bogotá aprende de las experiencias de China y España para enfrentar el coronavirus. Agencia Anadolu. https://www.aa.com.tr/es/mundo/el-hospital-militar-de-bogotá-aprende-de-las-experiencias-de-china-y-españa-para-enfrentar-el-coronavirus/1783396

- Acosta, L. J. (2020, March 23). In battle against coronavirus, Colombia transforms military hospital. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-colombia-idUSKBN21A3IT

- Christoyannopoulos, A. (2020, April 7). Stop calling coronavirus pandemic a “war.” The Conversation. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from http://theconversation.com/stop-calling-coronavirus-pandemic-a-war-135486

- Malafouris, L. (2020). Thinking as “Thinging”: Psychology With Things. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419873349

- Adler, S. R. (2011). Sleep Paralysis: Night-mares, Nocebos, and the Mind-body Connection. Rutgers University Press.

- Yoshimura, A. (2015). To Believe and Not to Believe: A Native Ethnography of Kanashibari in Japan. The Journal of American Folklore, 128(508), 146–148. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerfolk.128.508.0146

- Ginsburg, F., & Rapp, R. (2013). Disability Worlds. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 53–68.

- Casey, C. (2020, April 7). COVID-19’s isolated world is the norm for people with disabilities. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/covid-19-isolation-disabilities/

NOTES

[1] Believed to be created in 2009 by Something Awful forums user Eric Knudsen, Slender Man is a fictional character with evolving appearances, motives, habits, and abilities. He is frequently described as a tall, thin man, dressed in a suit and tie, with a white, featureless face and unusually long tentacle-like arms. On May 31, 2014, two 12-year-old girls in Waukesha, Wisconsin stabbed a classmate multiple times, in an attempt to become “proxies” for Slender Man. Learn more about Slender Man at https://alumni.berkeley.edu/california-magazine/just-in/2018-10-31/slender-man-perfect-monster-our-time.

[2] Momo, a creature with bulging eyes, a beak-like mouth, and human breasts resting on a bald, chicken-like body with avian feet, was reported in 2018 to have lured children and adolescents around the world into performing life-threatening tasks, such as self-harm, suicide, and violent attacks. Authorities and the media advised parents to monitor their children’s online activity. Learn more about the “Momo challenge” at https://www.vox.com/2019/3/3/18248783/momo-challenge-hoax-explained.

[3] Cuomo referred to “it” using militarized language as New York residents began facing exponential increases in new cases and casualties in March 2020.

[4] Cyril Ramaphosa donned a camouflage uniform while riling up soldiers in the Soweto township of South Africa’s Johannesburg to “defend our people against the coronavirus” during a three-week nationwide lockdown that went into effect on March 27, 2020.

[5] In preparation for “it,” Clara Esperanza Galvis, the director of Colombia’s central military hospital, led the opening of a hospital which had previously housed injured security force personnel at the height of Colombia’s armed conflict between leftist rebels, the government, drug cartels, and right-wing paramilitary groups.