Autumn Leaves: translating a jazz standard to the visual medium

by Jake Lesher

It was like a bridge between sound and color. When Thomas Young conducted his now famous double slit experiment in 1801, he observed that light passing through two parallel apertures did not yield two bright spots, as is expected of a particle, but rather, as Young describes them, “undulations”1, which marked the first recorded observation of light’s wavelike properties. Young would go on to measure the specific wavelengths and frequencies of different colors of light.

Sound waves share many characteristics with light waves, even if they do not share the same sensory organ. For example, many musical metaphors reference sight, or more broadly, spatial perception as a whole. The most extreme form of this association between music and light occurs in individuals with sound-color synesthesia. However, these metaphors are ubiquitous among not only individuals, but entire cultures: “high” and “low” notes, “bright” and “dark” tones, “thick” and “thin” melodies.

We can apply these vibrational metaphors to our physiology as well; as Céline Frigau Manning put it, the relationship between tuning strings on a musical instrument and nerve tension in the body transcends the figurative and becomes a literal way of understanding the body.2 Movement produces nervous vibrations in the body independent of auditory or visual perception, further suggesting that vibrations of one modality are not tied to their medium, and have the potential to be translated to another.

Because they are shared by both music and color, the quantifiable elements of wavelength and frequency — when coupled with linguistic metaphors that bridge sound and color — allows for an atypical representation of music in the visual realm. By translating a popular jazz composition to the visual realm and beyond black and white sheet music, I will highlight abstract elements of music theory in a more readily apparent and comprehensive way.

NOTES

- Thomas Young, (November 12, 1801), royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstl.1802.0004, 16.

- Frigau Manning, Céline, Tillmann Taape, and Lan Li. Hypnosis & Musical States of Mind. Other, n.d., 14:17.

Captions

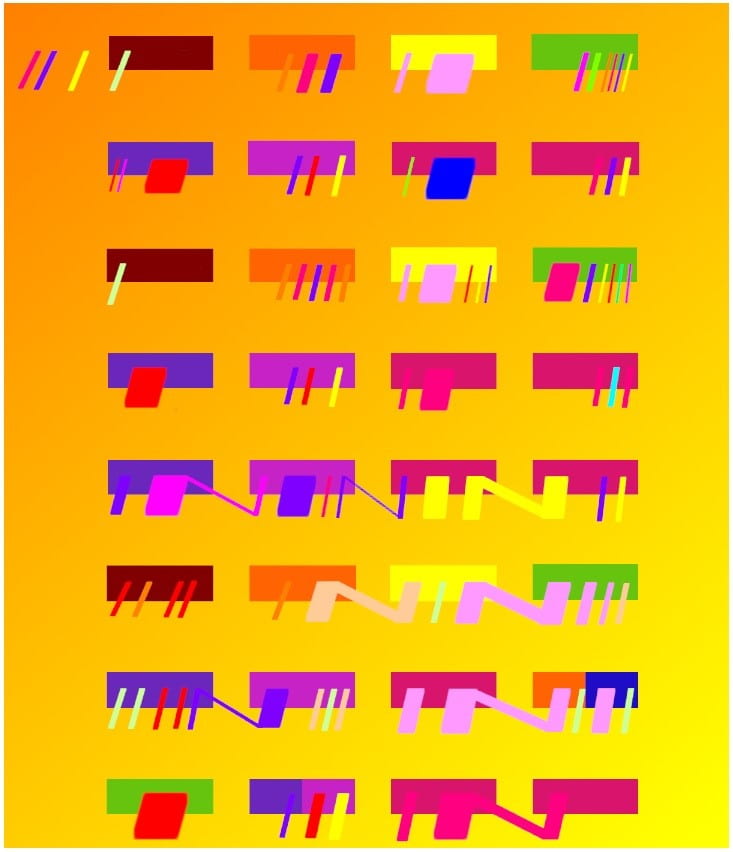

To capture elements of music to be portrayed in a visual medium, I began with synesthetic associations between musical notes and color. Although musicians with grapheme-color synesthesia may associate particular colors with notes on a page (e.g. the note “A” might be red), but this sensation is merely an association between colors and the concept of letters, not the notes themselves. I decided to take this association one step further and assign each note on the twelve-note chromatic scale a particular color, corresponding to its position of its eponymous key on the circle of fifths. The closer two keys are to each other on this circle, the more notes they have in common, which I extended into my color assignments. For example, D is followed by A is followed by E on the circle, and these three notes correspond to orange, red, and magenta, respectively. I extended this color correspondence beyond notes, and also applied it to the chord progression, key, and repeated motifs of “Autumn Leaves”.

The first two phrases of “Autumn Leaves” are almost entirely identical, which is indicated by the repetition of the same shapes and motifs in the first four lines of my translation. However, the second phrase is often played one octave higher, which I portrayed using lighter versions of the same colors, in accordance with the strong association between high/low pitches and bright/dark colors among both synesthetes and the general population.

References

Chet Baker. Autumn Leaves. She Was Too Good To Me. Van Gelder Studio, NJ: Creed Taylor, 1974. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgn7VfXH2GY.

Frigau Manning, Céline, Tillmann Taape, and Lan Li. Hypnosis & Musical States of Mind. Other, n.d. https://cargocollective.com/mind-metaphors/STATES-OF-MIND

Miles Davis Sextet. Autumn Leaves. Somethin’ Else. Blue Note Records, NJ: Alfred Lion, 1958. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u37RF5xKNq8.

Shayan, Shakila, Ozge Ozturk, and Mark A. Sicoli. “The Thickness of Pitch: Crossmodal Metaphors in Farsi, Turkish, and Zapotec.” The Senses and Society 6, no. 1 (2011): 96–105. https://doi.org/10.2752/174589311×12893982233911.

Ward, J, B Huckstep, and E Tsakanikos. “Sound-Colour Synaesthesia: to What Extent Does It Use Cross-Modal Mechanisms Common to Us All?” Cortex 42, no. 2 (2006): 264–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70352-6.

Young, Thomas. “On the Theory of Light and Colours.” The Bakerian Lecture. Lecture, November 12, 1801. royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstl.1802.0004.